Notions of creation and beauty are commonly considered synonymous with the very meaning of art, however determined they may be by changes in historical taste. Such concepts rarely include destruction as a characteristic of beauty, a condition of creation, or a fundamental component of art. The dialectic of destruction/creation and its synthesis in art have been neglected in the etiology of creation

Destruction in art is not the same as destruction of art.(2) On the plane of form, destruction in art introduces destructive processes into the actual making of an object or event, and on the level of subject matter, it is not only an examination of the meaning and presence of destruction in the creative process but in life in general. As a conveyor of content, destruction in art is a theme which critiques the autonomous character of the traditional arts as these productions have been isolated and defined within various systems of historical discourse and its markets. As signification, destruction in art attacks the traditional identity of the visual arts but not actual art practices such as painting and sculpture. Destruction in art should be understood as a method employed to expose habits of theory and practice that deterministically narrow artistic production and its public reception. In a general way, destruction in art metaphorically addresses the negative aspects of social and political institutions, within which life-threatening technology and psychic practices have evolved and, in a specific sense, it examines conventions which constrict the constructive capacity of the individual.

All of these issues were brought into focus at the Destruction in Art Symposium which took place throughout the month of September 1966 in London. More than fifty artists and poets from ten countries in Europe and North America met there to participate in a three-day symposium and to perform events or create objects in a wide range of media throughout the month. (3) The majority of those who participated were visual artists who had been instrumental in the development of Happenings, or were poets who had created visual and phonic (Concrete) poetry. An equal number of artists from as far away as Argentina, Japan, and Czechoslovakia either sent photographs, original works of art, documentation, or theoretical texts to be read or exhibited at DIAS. (4)

The diverse collection of artists who participated either directly or indirectly in DIAS were unified in their response to the theme of destruction in art. Yet they never comprised a movement nor produced a manifesto or publication.(5)

They never established a meeting place to discuss and share ideas, nor did they exhibit as a group again after DIAS. Apart from the month of events, DIAS simply represented a special moment in which a small body of artists shared a discriminating attitude about the use of destruction as an element in the creation of art, as a conceptual frame, as an attitude to the world, and as a way of relating subject matter in art to events and conditions in society. This attitude permitted them to explore a body of thought and aesthetic action of intellectual, social, political and aesthetic consequence.

DIAS was conceived and orchestrated by the stateless artist, Gustav Metzger.

He was primarily assisted by John Sharkey, an Irish poet working with visual (Concrete) poetry, a film-maker, playwright, and author who designed the DIAS poster and who, at the time, managed the gallery at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Seven years before DIAS, on November 9, 1959, Metzger authored the manifesto Auto-Destructive Art, the first of five manifestos written between 1959 and 1964.

AUTO–DESTRUCTIVE ART

Auto-destructive art is primarily a form of public art for industrial societies.

Auto-destructive painting, sculpture and construction is a total unity of idea, site, form, colour, method and timing of the disintegrative process.

Auto-destructive art can be created with natural forces, traditional art techniques and technological techniques.

The amplified sound of the auto-destructive process can be an element of the total conception.

The artist may collaborate with scientists, engineers.

Auto-destructive art can be machine-produced and factory-assembled.

Auto-destructive paintings, sculptures and constructions have a lifetime varying from a few moments to twenty years.

When the disintegrative process is complete the work is to be removed from the site and scrapped.

London, 4th November, 1959

From 1959 until 1966, when he created DIAS as a forum for other artists to expand the dialogue he had begun on destruction, Gustav Metzger realized his socially motivated, inherently political theory and practice of Auto-Destructive Art in such works as public lecture-demonstrations (1960-1966), in the development of an acid-nylon technique for painting (1960-1962), in very early

(1963-1966) projections of liquid transforming crystals, and in his visionary projects for auto-destructive sculptures to be erected in public places. In his Manifesto World of June, 1962, Metzger berated the "stinking fucking cigar smoking bastards" and "scented fashionable cows who deal in works of art" and called for the artist to "destroy art galleries…(the) boxes of deceit" that represent "capitalist institutions." (6) Such a destruction, he urged, was a means to create a new realism capable of showing "the importance of one object" or the "relationship between a number of objects" and was the first step to the formation of a theory of aesthetics that might include *the total relationship of objects including the human figure."

Gustav Metzger was the first artist to systematically identify destruction as the essential theme of, and dilemma in, modern life. He then incorporated his findings in a comprehensive reappraisal of art and its potential role in society.

His special contribution resided in the conjunction of formal innovation and historical circumstance; he analyzed the phenomena of the destruction of materials through change, chance, and indeterminacy as the basis of kinesis and destruction in political, psychological and social material. He provided an aesthetic equivalent to destruction by collapsing form, subject matter, and content into a single plane of expression in a self-decomposing and deconstructing object. While other artists such as Jean Tinguely, Yves Klein, Arman, Bernard Aubertain, certain members of the German based ZERO group, and Fluxus at times employed destructive means in their work, no one except Metzger so thoroughly recognized and pursued the full ramifications of this problem. (7)

Metzger's work demanded not only a political reading of art, but an engaged and self-conscious relationship to its production. His concern for the international, interdisciplinary scope of destruction in art was most clearly brought out in the first press release he wrote for DIAS, where he explained that:

The Destruction in Art Symposium…will bring together artists from various countries…writers, psychologists, sociologists, and other scientists. The main objective of DIAS is to focus attention on the element of destruction in Happenings, auto-destructive art, and other new art forms, to relate this to destruction in society.

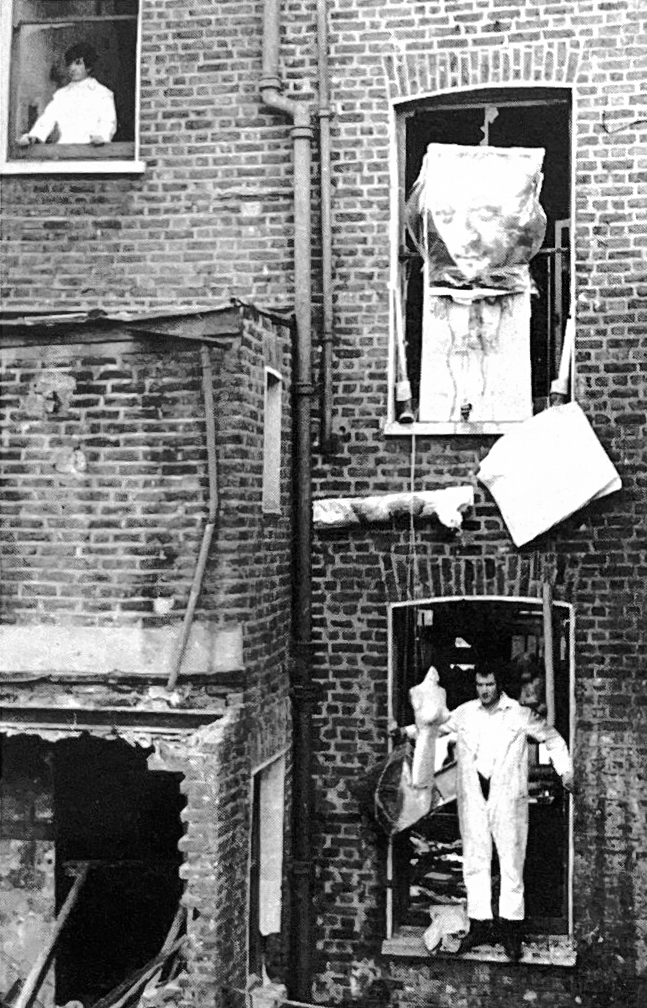

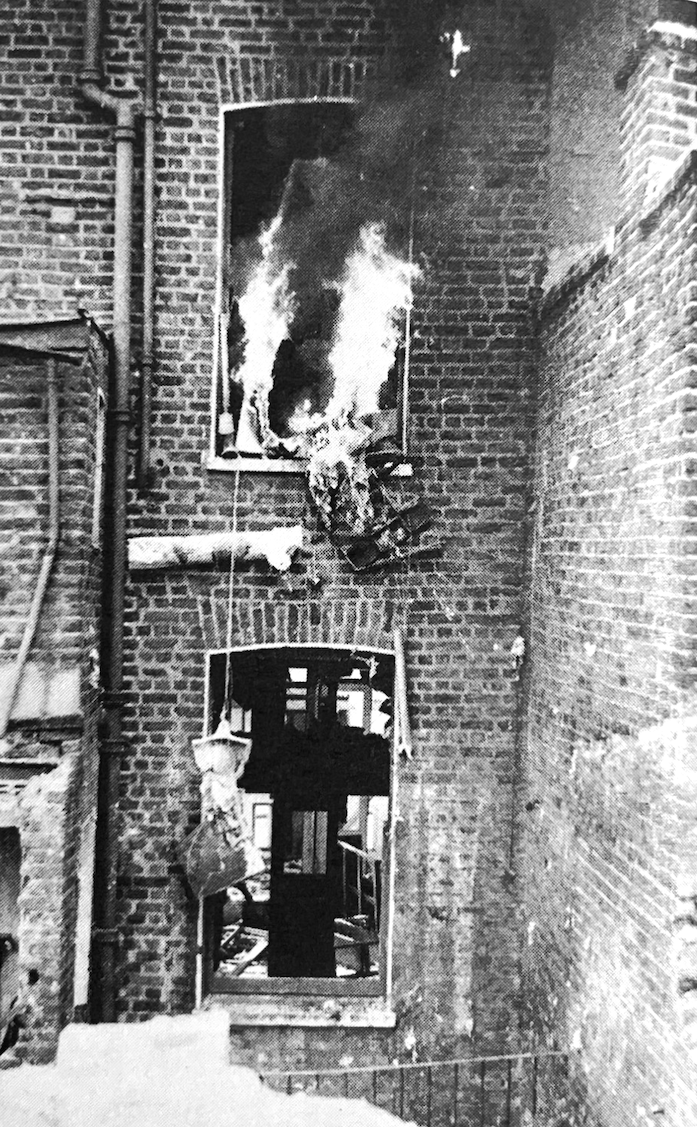

Ivor Davies performing "Robert Mitchum Destruction/Explosion Event" on Porto Bello Rd., near the Free School PLayground, London. September 13th, 1966. Photo: Michael Broome.

Only a few artists at DIAS worked with natural forces such as destruction wrought by wind, fire, rain, air, water, or gravity. Foremost among them, Graham Stevens created a massive pneumatic structure into which the public was invited to experience the heaving, swaying, and constantly changing shape of nature. (8)

Juan Hidalgo of the Spanish ZAJ group, often associated with Fluxus activities, performed his colleague Tomas Marco's Mandala ,during which a candle burned silently for one hour, one minute, one second.

The events in which DIAS artists utilized the body to signify the destructive and violent conditions affecting the individual ranged from private, psychological and spiritual experiences, to public and social experiences.

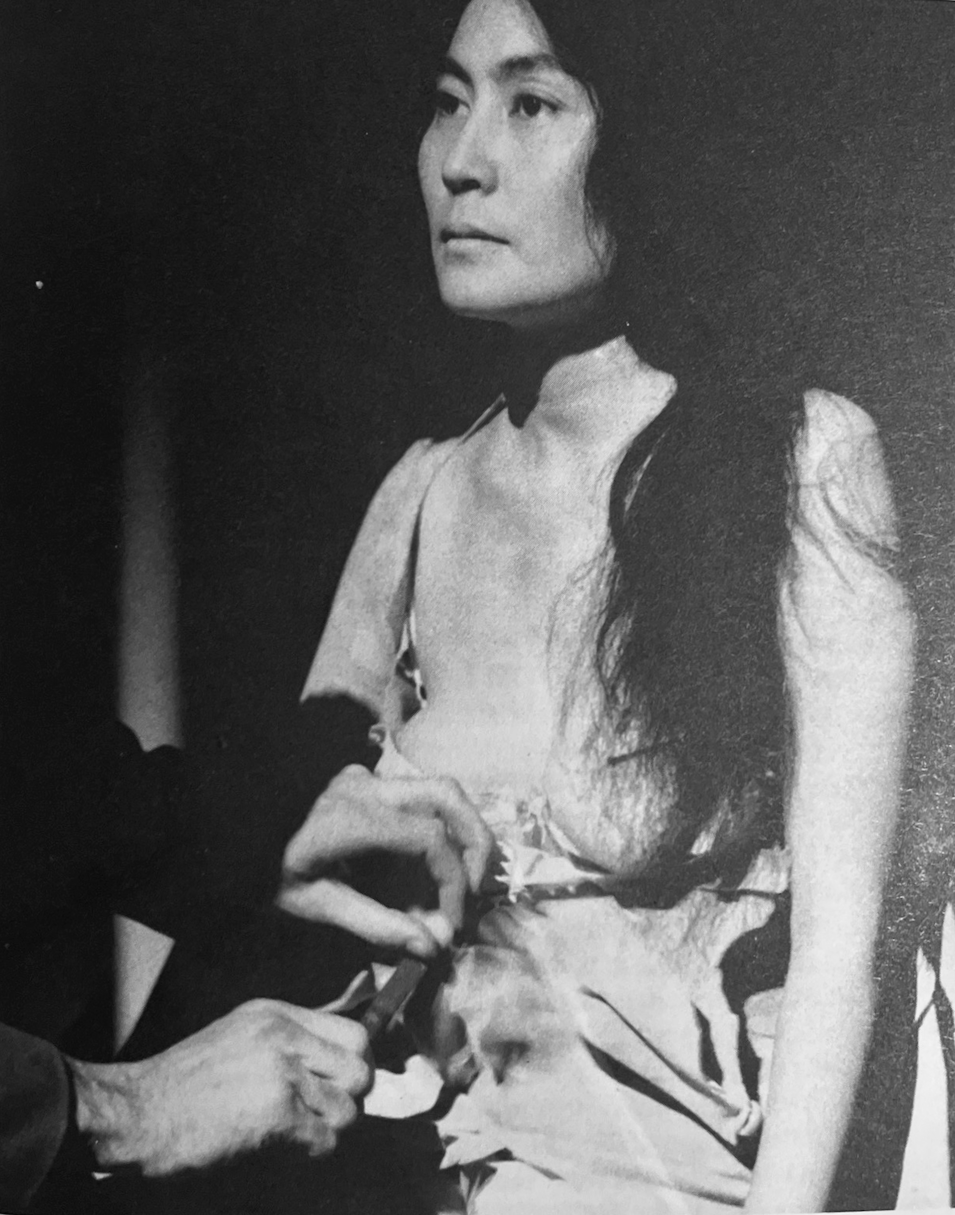

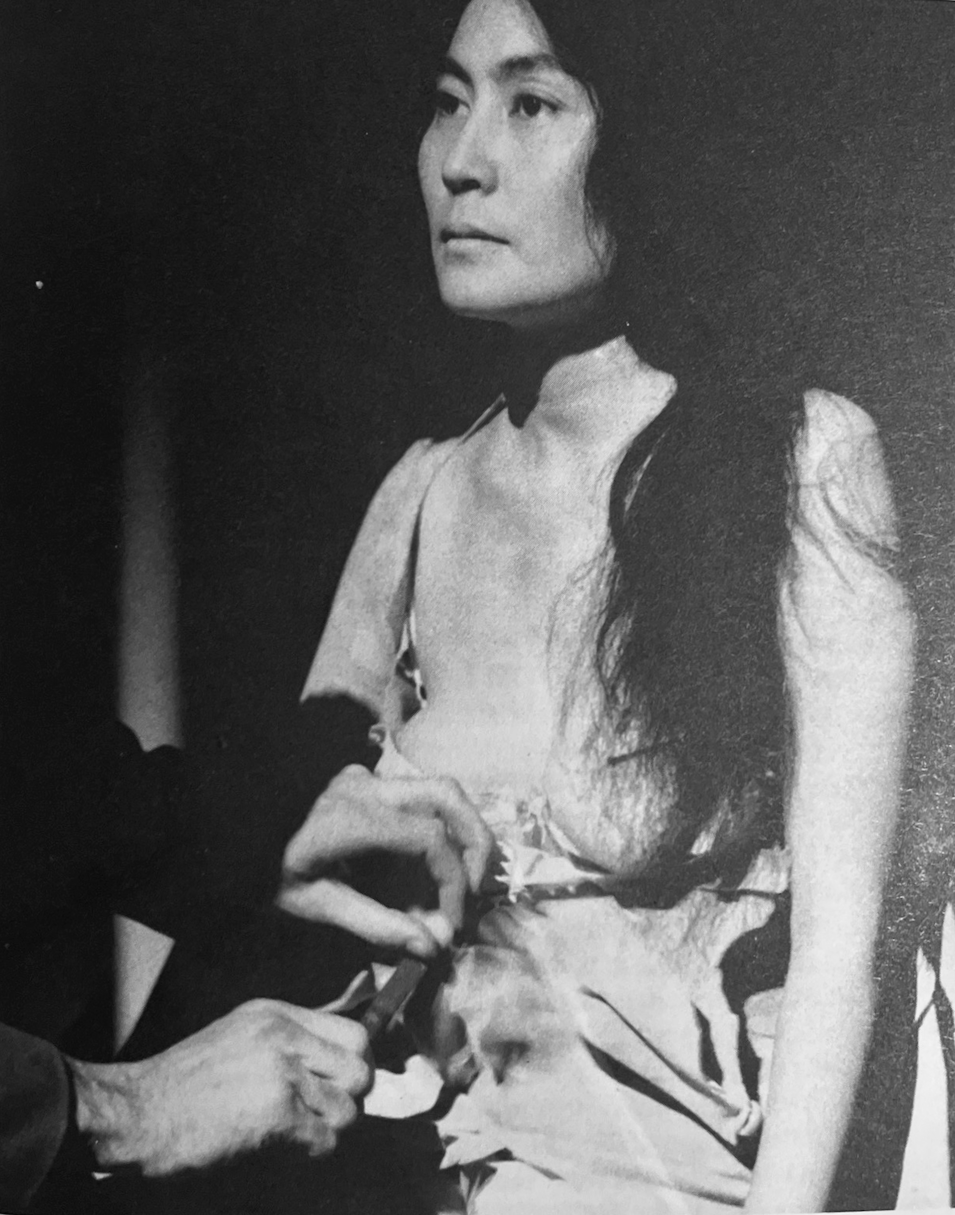

Powerful among these were Yoko Ono's Cut Piece in which she sat passive and immobile after having invited the audience to come to the stage and snip away her clothing. In Rafael Ortiz's event, Self-Destruction, Ortiz ripped his suit to reveal himself dressed in diapers. Whining, screaming, cajoling, and desperately calling, "Mamma, Ma Ma Ma Ma" and "Pappa, Pa Pa," he banged a rubber duck and drank enormous quantities of milk from bottles until he vomited on the stage, bringing his psychic Oedipal drama to an end. These kinds of physical actions stood at the apex of DIAS activities but none more than the presentation of Hermann Nitsch's Orgies Mysteries Theatre.The artists who witnessed Nitsch's work at DIAS were nearly unanimous in their agreement that Nitsch and the Austrians had pushed the possibility for visual expression to the limit.

Powerful among these were Yoko Ono's Cut Piece in which she sat passive and immobile after having invited the audience to come to the stage and snip away her clothing. In Rafael Ortiz's event, Self-Destruction, Ortiz ripped his suit to reveal himself dressed in diapers. Whining, screaming, cajoling, and desperately calling, "Mamma, Ma Ma Ma Ma" and "Pappa, Pa Pa," he banged a rubber duck and drank enormous quantities of milk from bottles until he vomited on the stage, bringing his psychic Oedipal drama to an end. These kinds of physical actions stood at the apex of DIAS activities but none more than the presentation of Hermann Nitsch's Orgies Mysteries Theatre.The artists who witnessed Nitsch's work at DIAS were nearly unanimous in their agreement that Nitsch and the Austrians had pushed the possibility for visual expression to the limit.

Yoko Ono performing Cut Piece at Africa Centre, September 29, 1966. Photo: John Prosser.

In the late 1950's. Nitsch had begun to construct an aesthetic theory analagous to the collective, violent, and destructive inheritance that he believed shaped Western civilization. He drew upon three traditions: the savage crucifixion of Christ; the legend of the ferocious, erotic, and paroxysmal Dionysian rites and mysteries; and the mixture of wounding, suffering, and sexual taboo in the collective guise of the Oedipus legend which informs Freudian psychoanalysis.

He combined these sources into a directly experienced action which, he theorized, might induce a cathartic or abreactive response in viewer-participants, cleansing them of destructive impulse.

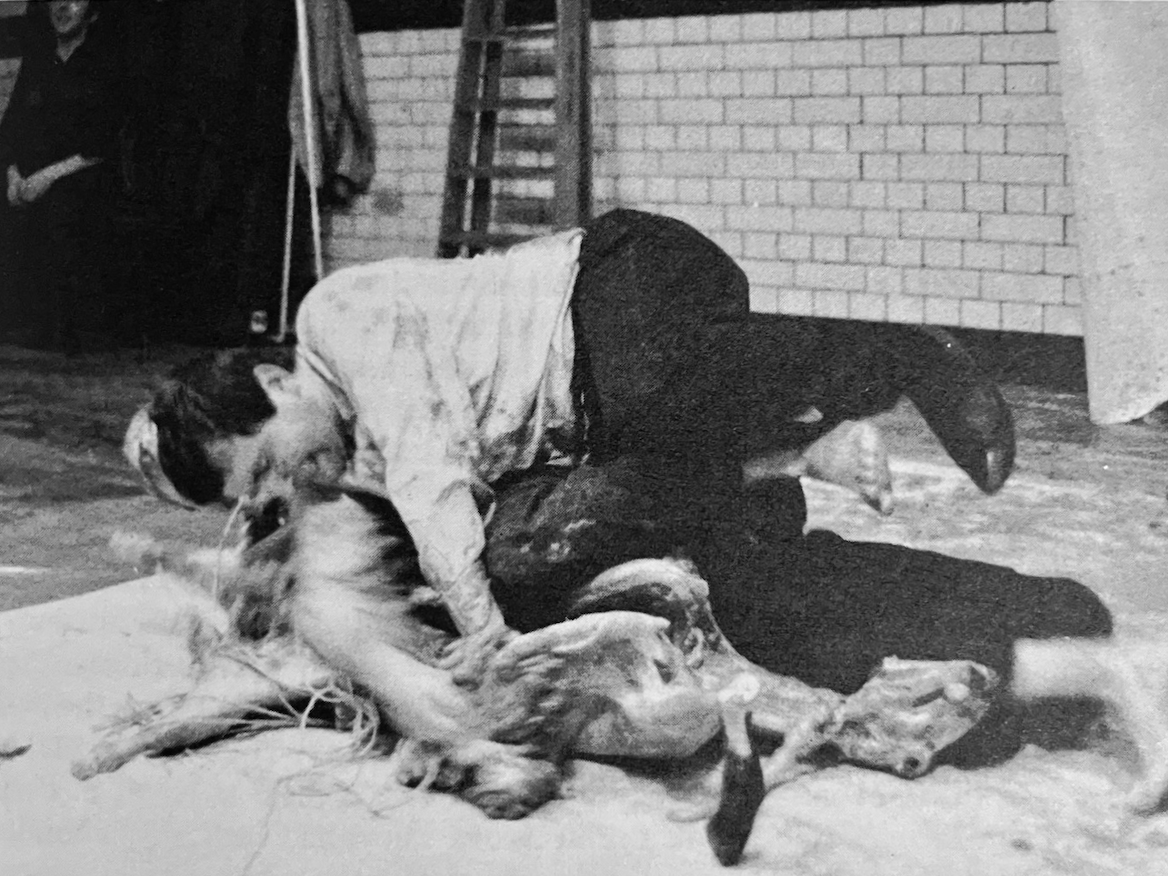

On the night of September 16th, with the help of Günter Brus, Otto Mähl, AI Hansen, and with participation from the audience, Nitsch presented his fifth abreaktionsspiel in a meeting room of the St. Brides Institute, which was attached to London' historic St. Brides Church. During the action, a lamb carcass was strung up, beaten, and mutilated. Animal viscera and offal were scattered about the area of action. Red paint, simulating blood, was poured over the dead flesh of the animal and its organs. A film showing images of male genitalia immersed in viscous fluid and manipulated by strings was projected on and off the flesh of the suspended lamb carcass, while percussive sounds of whistles, rattles, and other instruments punctuated the action. (It is noteworthy that, at DIAS, Nitsch first introduced sound into his work. The orchestration of his own music would subsequently become a component that would form a critical part of the structure of his work.)

Two Associated Press journalists reported Nitsch's action to the police, who arrived near the end of the performance. Metzger and Sharkey were given a summons to appear before a London Magistrate on the charge that they, in exhibiting Nitsch's work, had presented an "indecent exhibition contrary to common law." Ten months after DIAS, and after the Magistrate had assigned the pair to a trial by Jury, Metzger and Sharkey stood accused for three days in July, 1967, at London's famed Old Bailey. The real threat of a maximum six-year prison term hung over their heads regardless of the fact that they had the artists indemnify them, prior to participation in DIAS, against responsibility for the destruction of material and/or the possibility of danger to life and property.

The verdict of the trial relied upon a series of photographs taken during Nitsch's event. The critical role of photography in recording and communicating the objective conditions of an action emerged as an unanticipated but salient feature of destruction-in-art events. Regardless of the fact that the photographs were re-presentations of a past action, they were presented to and understood by the jury as the primary account and record of the original event. Much testimony on behalf of the defendants pointed out that the photographs dramatically altered the context and feeling of the performance, since they isolated the various actions and images from their original continuity, simultaneity, and kinesthetic sequence in the event. Yet, on the basis of the prosecution's careful selection of photographs presented as evidence of the "indecent" nature of Nitsch's art, Metzger and Sharkey were ultimately found guilty of the charge.

Both were sentenced lightly.

Since the photographs stripped the serially developed action of its unity, they raised questions of a more general nature about the conditions and responsibility of documentary photography. It is well-known that photographs distort and misrepresent information, that they are not images of reality any more than reality may be perceived as a static object for contemplation. The DIAS trial, however, raised a question seldom asked of such photographs: With whom rests the responsibility for interpretation of the artistic intent and content of an action mediated by a photograph: the artist, the photographer, the sponsors of the exhibition, the viewer?

This problem poses even more serious considerations if the photographs – which may or may not distort an art action – tend to be of a particularly destructive, violent, and/or pornographic nature, or are salacious or scandalous in content and suggestion, offering no real sense of the conditions of the original event. Some photographs produced by the Austrian artist Rudolph Schwarzkogler provide an example. Schwarzkogler set up tableaux of castration for the purpose of producing a series of photographs. Although Schwarzkogler used the artist Heinz Chibulka as his model for the photographs, some of which pictured a male figure whose penis was swathed in gauze, stained with blood, and resting on a table before him, the images were understood by viewers to be representations of Schwarzkogler's self-mutilation. A story circulated that Schwarzkogler's death in 1969 (the photographs were taken in 1965) had occured as the result of a castration performance and this myth was internationally perpetuated by Robert Hughes in Time.(9) How will future artists transform and interpret provocative works by artists such as Chris Burden, Gina Pane, Nitsch, Mühl, Brus, and Ortiz, when the photographic document is considered primary and equal to the event?

Hermann Nitsch performing Fifth abreaktionsspiele, Orgies Mystery Theater, St. Brides Institute, London, September 16, 1966. Photo: John Prosser.

In Spring 1966, the late Mario Amaya, then editor of the fledgling publication Art and Artists, worked with Metzger to produce a special August issue on

"Violence in Art" which featured many DIAS artists. DIAS events also attracted wide international media coverage, culminating in the February 12, 1967 cover story for Life which labeled DIAS the "underground" of Happenings—

the

"Other Culture." However sensational, DIAS and the destruction-in-art exhibitions which followed it (10) lapsed into obscurity, an obscurity which testifies to the provocative challenge of DIAS and its assault upon widely held ideological assumptions at the core of art, culture, and society. The marginalization of DIAS events and artists also testifies to the historical viability of such art and artists, especially when compared to the current fashion for tailoring art to be marketed and consumed as political art—the liberal intellectual's aesthetic placebo for political activism.

DIAS left emanations well-outside the radius of its frame, theme, historical place, and time. In psychoanalysis, the pop-psychologist Arthur Janov attributed the account, which one of his patients gave him, of the performance Self-Destruction (which Ortiz did at the Mercury Theatre during DIAS) as the basis for his development for the Primal Scream technique. (11) The effects of DIAS surface in political events, especially in the May 1968 student revolt in Paris, in which Jean-Jacques Lebel took a central role. Lebel had earlier collaborated with the Situationistes Internationales and was active in the climate that produced Guy deBord's 1967 tract, "On the Poverty of Student Life," a text well-known to have agitated students at the University of Strasbourg, and which also influenced the May events in Paris. Ortiz and Jon Hendricks used elements of Nitsch's work in a massive protest march on Washington when, together with an agit-prop group, they were pictured in Timecarrying bloodied lamb heads to symbolize the carnage of the Vietnam War. Peter Townshend of The Who has acknowledged that it was Metzger's Auto-Destructive Art

lecture-demonstration in 1962 at Ealing Art School (where he was an art student at the time) that directly influenced his decision to use destructive elements such as smashing his guitar to splinters in eroticized, frenzied, musical climax while performing.(12)

Out of the cacophony of events, press conferences, the symposium, parties, friendly jostling for power, attention, and influence that occurred in or resulted from DIAS, several important theoretical issues emerged. The trial of Metzger and Sharkey brought into sharp relief the problem of censorship which was rooted in the paradoxical core of the destruction/creation dialectic. Still insoluble are the moral, ethical, and aesthetic questions which surfaced then and remain enigmatic today. How far might the borders of art be stretched to accommodate personal, cathartic actions and destruction-as-art? The killing of animals under all conditions (even to support human life) and the destruction of matter and property (i.e., books, paintings – as in the case of works created by Werner Schreib, John Latham, Pro-Diaz, and musical instruments as in Ortiz's Piano Destructions )remain the subjects of bitter debate. What is the relationship between the freedom to explore authentic artistic impulse and an artist's responsibility to uphold and respect commonly held public values? (What is the real effect on viewers and participants when highly symbolic and organic materials such as blood are used?) Today, as in 1966, the definitions of pornography and obscenity are embroiled in gender and religious politics and are rife with fundamental questions of decency, the integrity of the body and mind, and respect for human propriety.

In addition to problems of censorship and the role of the documentary photograph that emerged at DIAS, DIAS events revealed the fundamentally radical form and content of Happenings which had been clouded by subject matter other than destruction. The alternative paradigm for artistic practice inherent in event-structured art consisted essentially in the role in which the human being functioned as a materialization of the contiguity of life with art.

The artist, by literally acting as the mediator between the two, then, in philosophical terms, created an event that provided a link between the alienated Space of subject and object – linking the world of the viewer to the world of the art object through the transit of the body. The artist now inhabited the position traditionally occupied by the art object and, in so doing, mediated between the viewer and the meaning of the event. The alienation between subject and object was thereby reduced, although not resolved. In other words, the artist as being-in-the-world visualized the contingency and inter-dependence of subject identifying with subject.

I would like to suggest that this alternative paradigm was accomplished by shifting from the visual arts' traditional and exclusive dependence on the communicative mechanisms of metaphor to those of metonymy. (13) A metonym is a figure of speech like a metaphor. Unlike metaphor, which operates through replacement, metonymy functions through connection, by creating a direct link between two proximate persons, events and/or objects. Some philosophers of language have even suggested that the metonymic process precedes the signifying capabilities of metaphor.

For metaphor, we must envisage a certain structure, i.e., perceive and interpret a metonymy, an expression like copper beard is to be interpreted 1). beard =

bearded man (metonymy); 2). copper = red (metaphor). Neglecting the

metonymy we run the risk of misinterpreting the metaphor: beard made of copper. Meaning is here dependent upon prior connective information – men have beards the color of which may be red like fire which can be described as copper – in order to understand the metaphor copper beard. (14)

Linguists have argued that meaning, conveyed through the metonymic operation,

requires a structuring along the axis of combination (a perception of contiguous

relations)…and deals with human relationships…through reduction to a less complex and usually more concrete realm of being. (15)

In DIAS events, metonymy functioned as a connective tissue that joined the destructive aspects of real-time events to the symbolic expressions of them in art. Through the signifying body, the artist was able to create a means to express the corporeal threat at the very base of social and political experience.

Functioning as a live vehicle of transit, the body operated as a synapse demonstrating the contiguity between art and life as well as the inexorable human link between subject and subject. This is not to say, as has been suggested by others, that a "universalization of categories" or a totality was created, but rather that the body in live, performed art operates as a means of association and juxtaposition like a connector, a bridge, a synapse, between two mutually identifying human beings. (16)

It was no coincidence that the art action – an art form animated by the dynamic structure of an event (a Happening) – appeared at a point where painting and sculpture were no longer able to effectively realize the political and social ramifications of the fragility of existence in the wake of the devastations of World War II. By introducing the artist's own bodily presence as the material work of art, these artists permanently altered the ways in which social issues might be presented in the visual arts. By situating the signifying body at the center of destructive events, they found a means to link creative values in art to the existential dilemmas of the nuclear age and stressed, finally, existence over essence.

I would like to close with the suggestion that, by reintroducing the living figure into experimental art and presenting the body as an object in and of historical circumstance in an avant-garde context, the DIAS artists radically revalidated the historic privilege which had been accorded the representation of the figure in painting and sculpture before the advent of Modernism.(17) The communicative power of figuration in experimental art was thereby restored, reinvigorating the strategies of avant-garde practice at the precise historical moment that Modernism floundered and was pronounced "dead" by many critics.

By presenting the living figure as form, subject matter, and content, destruction-in-art works condensed and displaced paradoxes of destruction and creation experienced only indirectly as historical events. The presentation of the threatened body can be argued to have also played a role in the strong reemergence of the existential figure in Action and Body Art and, however subliminally, in Neo-Expressionist painting and sculpture, where the human being is often represented as politically and/or psychologically threatened. At the very least, the strength of the figure in recent art owes a tremendous historic debt, not only to the twenty years of live art that preceded it, but to the achievements of those who struggled to penetrate the meaning of destruction in their artistic practice.

Twenty years after DIAS, it has become an historical object, not only a reflector of its period, but a subject of study which reveals the significance of the often historically invisible on the too-often insignificant visible. DIAS dramatised what was already apparent but remained unaddressed. In this way, the DIAS artists were a society's sentient antennae who, with highly cultivated consciousness, quickly responded to the ethos of the post-World War II period and constructed an image of some of the most problematic experiences of art in our time.

London Free School Playground. Site of DIAS events. Gustav Metzger in foreground carrying plastic bag with found objects. September, 1966. Photo: Hans Sohm.

NOTES

1. September 1986 marked the twentieth anniversary of DIAS. I began the reconstruction and analysis of this event for my doctoral dissertation entitled The Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS): The Radical Cultural Project of Event-Structured Art at the University of California, Berkeley in 1980 under the direction of Professors Peter Seiz, Herschel B. Chipp, and Martin Jay. I am as indebted to their support and insight as to that of the artists with whom I have worked these past six years, especially Gustav Metzger, John Sharkey, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Wolf Vostell, Rafael Ortiz, Ivor Davies, Otto Möhl, and Hanns Sohm, the extraordinarily inventive and dedicated archivist of Happenings and Fluxus, whose archive now exists in the Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart. A special thanks to Jacques Chwat, Jeffrey Greenberg. Jan Peacock, and The Act for their astute editing of a much longer text.

2. Art is here defined broadly as that generic endeavour of causing, founding, originating, bringing about, or giving rise to observable results in the form of sensate or psychological, perceptual phenomena and/or actual objects.

3. Among those who participated in DIAS not named in this essay were Mark Boyle, Barry Flanagan, Jeff Nuttall, Criton Tomazos, Cornelius Cardew (England); Kurt Kren, Peter Weibel (Austria); Henri Chopin (France); Wolf Vostell (Germany); Jean Toche (U.S.A.): Luis Alberto Wells (Argentina); Robin Page (Canada); Jose Luis Castillejo (Spain).

4. Kenneth Kemble and the Destruction Art Group, BEN, Robert Filliou, Ilse and Pierre Garnier (France);

Peter Gorsen (Germany): Milan Knizak (Czechoslovakia); Mathia Goeritz (Mexico): Simon Vinkenoog, Herman de Vries (Holland): Ad Reinhardt, Philip Corner (U.S.A.); Tomas Marco, Manolo Millares (Spain):

Gianni Emilio Simonetti, Enrico Baj, Giuseppe Chiari (Italy); Diter Rot, (Iceland).

5. Wolf Vostell devoted issue No. 6 of his publication Dé-coll/age: Bulletin aktueller Ideen in 1967 to artists and texts related to DIAS and Metzger published a six-page handbill entitled "DIAS Preliminary Report. Apart from these two, no publication was undertaken about DIAS by any of the DIAS artists.

6. See "Manifesto World," in Metzger's Auto-Destructive Art: Metzger at AA, a booklet that Metzger published on the talk he delivered to the Architectural Association of London in February, 1965 (available in the Sohm Archive, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart).

7. The actual DIAS Committee was made up of an international body of artists and intellectuals who helped to shape the structure of this massive event. The committee included Dom Sylvester Houedard, a Benedictine monk from Prinknash Abbey in Gloustershire and critical figure in the development of the Concrete Poetry movement in England, as well as Bob Cobbing, also a concrete and phonic poet who managed Better Books – a bookstore that functioned in the mid-1960s as a gathering place for the international avant-garde and underground. Mario Amaya, then editor of Art and Artists; Ivor Davies, a Welsh Painter working on his doctorate and teaching at the University of Edinburg; Roy Ascott, an artist and innovative art educator, then director of the Ealing School of Art, the American Jim Haynes, then a member of the editorial board of the International Times (IT), and 'Miles,' an ever-present figure in the London Underground who ran the avant-garde bookshop and gallery in London called Indica, as well as Wolf Vostell, the German creator of dé-coll/age Happenings, Enrico Baj, an Italian painter, and Frank Popper, the influential critic of Kinetic and Optical art then living in Paris.

8. John Rydon of the London Daily Express featured a photograph of Metzger and cited his Auto-Destructive Art concept in that publication on November 12, 1959. On March 10, 1960, Rydon again reviewed Metzger and published a photograph of his first auto-destructive model for a public sculpture.

Tinguely realized Homage to New York on March 17, 1960. Before that time, the element of destruction had never entered his art, and even the total auto-destruction of Homage to New York was fortuitous,

9. Robert Hughes, "The Decline and Fall of the Avant-Garde," Time. December 18, 1972, p. 11. Edith Adam, Schwarzkogler's companion at the time of his death in 1969, was in the apartment the day the artist died, and has explained to the author that Schwarzkogler had been following a mystic health regime that had induced hallucinations from time to time. In a highly agitated and nervous state the artist fell, jumped, or thought he could fly from his apartment window in Vienna and fell to his death.

10. Both 12 Evenings of Manipulations which took place in the fall of 1967 and DIAS/NY: A Preview(1968) took place at the Judson Church. Both were organized by Rafael Ortiz and Jon Hendricks, future founder of the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAG). Destruction Art took place at Finch College in New York, 1968.

Ortiz and Hendricks ultimately cancelled their plans for an international exhibition on the scale of DIAS

London (which would have been entitled DIAS-U.S.A.), after the assassination of Martin Luther King. Ortiz and Hendricks published a statement:

In deference to the memory and the spirit of the beautiful soul of D. Martin Luther King. Jr. …

This is a time for the ceasing of all destruction – even that of art.

11. Arthur Janov, The Primal Scream: Primal Therapy: The Cure for Neurosis(New York: A Delta Book, 1970), pp. 9-11.

12. The Who, (New York; St. Martin's Press 1982), pp. 6-7.

13. I first discussed the relationship between the operations of metonymy and the alternative communicative functions of live, performed art with my students in 1979 while teaching a seminar on the history of Performance Art at the University of California Berkeley, to which I invited Laurie Anderson, Tom Marioni, Chris Burden, and Linda Montano to speak on their work.

14. Jerzy Kurylowicz, "Metaphor and Metonymy in Linguistics," Zagadnienia Rodzajow Literackich 9 (1967), p.8. For a working definition of metonymy also consult Roman Jakobson's "Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances," in Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle's Fundamentals of Language (The Hague, Mouton, 1956).

15. Robert J. Matthews and Wilfried Ver Eecke, "Metaphoric-Metonymic Polarities: A Structural Analysis," Linguistics: An International Review 67 ( March 1971), p. 49. The authors quote Kenneth Burke's A Grammar of Motives (New York, Prentice-Hall, 1945), p. 504, where Burke explains that the strategy of metonymy is "to convey some incorporeal or intangible state in terms of the corporeal or tangible." This point is of particular relevance to the function and structure of the communicative potential of live, performed art – art structured in the form of events.

16. Thomas McEvilley's "Art in the Dark" Artforum 21 (Summer 1983) reprinted in Theories of Contemporary Art ed. Richard Hertz (New Jersey 1985), p. 288.

17. In 1983, this topic was the basis for the lecture "National Tendencies in Contemporary German Art." which I was invited to deliver to the Post-Graduate Interdisciplinary Summer Seminar in German Studies and German National Identity, conducted by Professor Tony Kaes at the University of California, Berkeley.

Aspects of this problem were presented in a talk I gave at the Walker Art Center, December 8th, 1986, entitled, "Contingent Life and a New Figuration." The paper dealt with Oskar Schlemmer's innovative integration of the figure into painting, theater and dance.