My involvement with performance art began in graduate school, in Athens, Ohio, in 1967, when I studied Allan Kaprow's "Happenings", the work of the Fluxus group, Yvonne Rainer and, in general, the early 1960's scene. I met Rae Davis in 1975 and have performed in several of her works, including Vanishing Acts, her most recent. Her influence on my own work, on my thinking, on the way I walk on the ground, has been profound.

Davis has been working with performance art in the relative isolation of London, Ontario, Canada since the early 1960's, some decade before the term

"performance art" gained currency. She had been writing and directing for the theater, but found what happened in rehearsal and behind stage more interesting than what was presented to the audience. She discovered also that her work was more appreciatively received in galleries.

The first work I saw by Rae Davis used three men. They were dressed in black, with bare feet, and were sitting on chairs some four feet apart from one another, staring toward the audience. Very, very slowly, with great concentration, one lifted his right hand from his leg, another lowered his head to his chest, and the third swiveled his feet on the floor from straight in front of his body to something like a 180-degree position. When the "foot" man and the "head" man completed their moves, Davis called the name of one of the performers, signifying the end of the piece. I liked it for its simplicity, for the concentration it demanded from performers and audience, and for the implications of its title:

Audition. (1)

Having performed in two subsequent presentations of the piece, I learned that slower is better; at its best, Audition took about ten minutes.

Imagine yourself extending the action of moving your head from an upright position to the point where your chin touches your chest through a ten-minute period. Imagine seeing three men moving imperceptibly. It might take three minutes before you are aware of movement; it might take five minutes before you identify the three separate actions; then, which one do you study?

Davis started work for Vanishing Acts in January, 1984, almost three years before its October, 1986 presentation at the London Regional Art Gallery. She began by studying the space for which it was commissioned and by taking notes on her current reading. The reading that led ultimately to the structure and content of Vanishing Acts included books on physics (especially David Bohm's investigations into quantum physics), The Tourist by Dean MacCannell, Rilke's The Duino Elegies and Aldo Ross's Scientific Autobiography. The few notes that follow, culled from hundreds of pages, are indicative of her preoccupations while thinking of the piece. (2)

Things do not happen in sequence but all together.

People see, think, assimilate multiple ideas with every glance. Art should insist that people use what they've got. (DR 18)

The actual immediate present is always the unknown. (PST 182)

By working associatively, something emerges which is not dependable, measurable, or exactly clear - there are handles and hooks to grab on to, but what is seen and constructed is put together by the person seeing it, experiencing it, etc. It reaffirms the shifting mysteries of being, an awareness of the energy of the unstated, but experienced sub-text that's a part of all our lives every minute of our lives.

If something is not considered a real possibility, there is no chance at all that it will appear among one's choices. (PST 203)

The divisions between "large" and "small," and between "simple" and complex," are of only a relative and limited kind of significance. (PST 261)

In performance, I wish to see all these polarities operating within a context where all is accepted at once and makes a time-situation, an experience/process situation of infinite possibility.

A. N. Whitehead: "Seek simplicity and mistrust it." (PST 312)

Again, the thought that autobiography - your inner self - is what you've got.

Though Davis gave performers specific directions in Audition and in other earlier works, we were always instructed to perform the action in as natural a way as possible, in other words, to "be ourselves." I found that the concentration required to sustain very slow movement turned my action into a form of meditation in which my sense of myself, of my presence, was intensified. I am more "myself," more self-aware, when I am working with Davis on a piece, and over the years, the kind of concentration I take to her work has influenced the way I live my life.

In more recent works, performers have had the opportunity to develop their own actions through improvisation. In other notes for Vanishing Acts Davis wrote:

There were eight performers in Vanishing Acts: four "movers" (two males and two females), who constantly occupied the space, and four "shakers" (two males and two females), who had brief appearances. The movers, of whom I was one, first met with Davis in late April (six months before the October performance date) to arrange a rehearsal schedule. There were to be forty-two rehearsals, two hours each, beginning the following month

At this first meeting, she asked us to get a picture of a place, an elsewhere, that was important to us; to write a message to someone important who no longer figured in our lives; to note habitual, perhaps unconscious, actions, and to think about 'folding.'

In May, each of us met individually with Davis. We gave her the messages we had written (these would be transmitted across an LED message board in the performance), told her about our habitual actions, moved with her through the space of her studio, and spoke about folding.

We talked about the picture of our important place and she taped our stories.

She later transcribed and edited these and had slides made of the pictures. (At intervals during the performance, each of the movers would read their own material while their slide was projected.)

Before the movers began meeting in June, Davis had determined the areas of the gallery to be used for the performance. The space is a voluminous gallery, crossed by a 22-foot-wide, black reflecting pool which is spanned by a concrete bridge and a metal grid platform leading to large elevator doors on a side wall On this same wall, at the second storey-level, there is a long passageway visible through a narrow window, and, on the opposite wall, a large window complements the elevator doors.

Rather early on, she decided to have a plywood slope built along the back edge of the pool with a wide platform along its top. Using the slope would give performers more presence in the large space and would provide a challenge for developing action. She also designed a system of risers for the audience along the opposing wall so that everyone could see the action, and so that their positions in the space would mirror those of the performers on the slope.

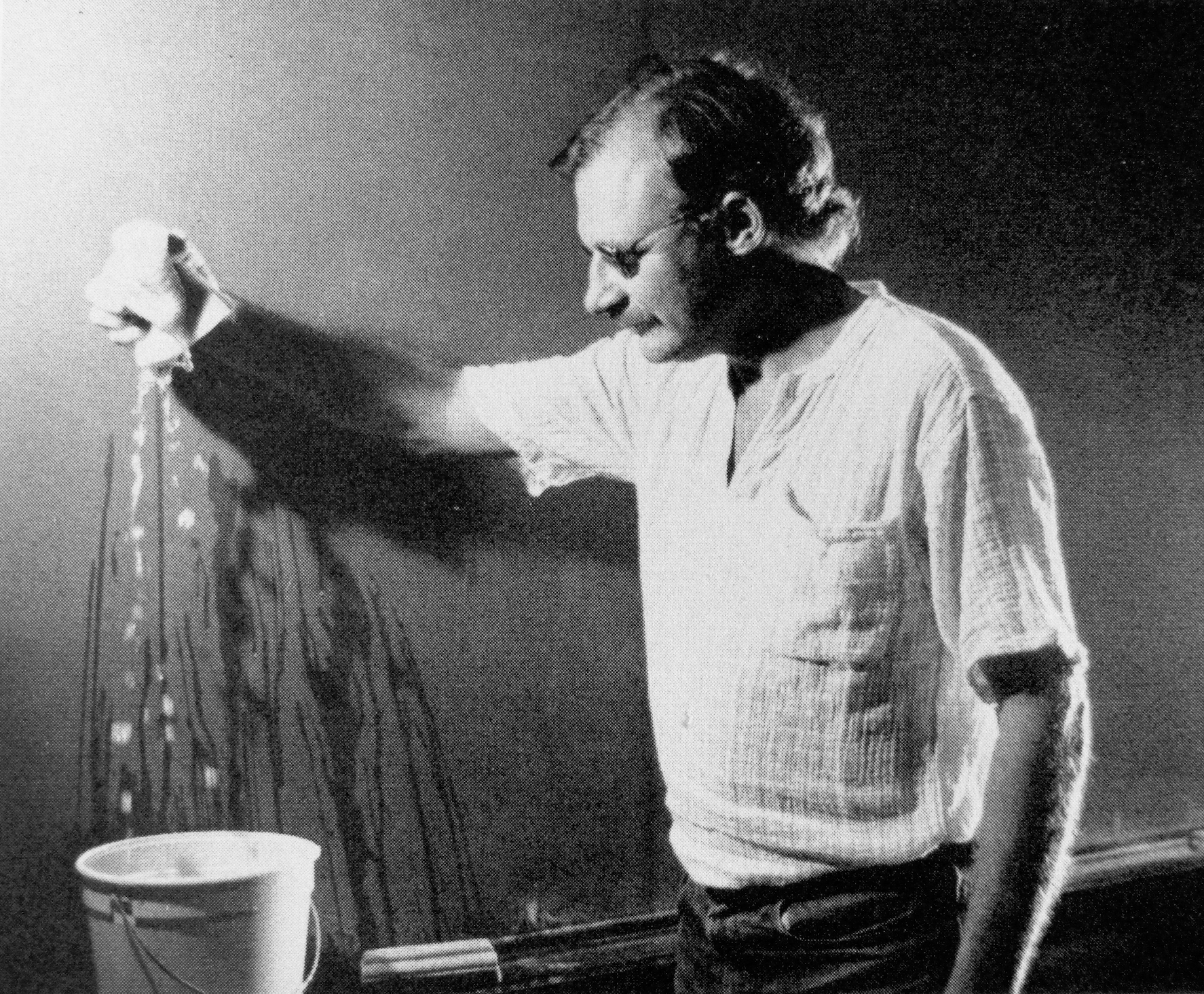

Robert McKaskell in Vanishing Acts. Photo: Martha Davis

In addition to the slope, we were to use the passageway behind the side wall (which we called "the cave"), the floor between the audience and the reflecting pool (on which she would place four platforms on wheels that could be used as independent structures or, placed in a row, as a second bridge), the concrete bridge and metal grid over the pool, and, behind the slope, an extension ladder with a platform.

Since we were not allowed access to the gallery until late August, rehearsals up until then were held in a smaller space, and our experience of the water, the cave, and the slope were mere projections. Her solution to the problem was simple: "We'll make a piece for this space," she said, "and using what we've learned, make a new piece for the gallery."

In the rehearsal space, she marked out the proportions of the gallery, indicating the pool and bridge. The cave was a separate area in the room and the platforms in the pool were represented by pieces of cardboard.

Our first rehearsals were spent in collective action - gaining our balance on the slope, learning the areas for use, and "playing" with various objects Davis provided. Those objects included a canvas bag filled with stones, a plastic rabbit and a ferocious looking foam dog, books, a mirror, various poles and sticks, a paddle, and a music box. Later, one person was asked to occupy an area or work with an object for five or ten (timed) minutes while the others watched, following which there was discussion.

This period of improvisation was exhilarating. The movers got to know one another, to be comfortable with one another through body movement, and to experiment with the objects. The mirror, for example, was used to double images of isolated body parts, to reflect light across surfaces of wall, and, like a "ghost" projector, to transmit images that had been drawn in the condensation from breath. We became concerned about how our movements felt and looked, and, at the same time, we were noticing our individual differences, our limitations, our idiosyncratic contributions to the piece.

By mid-July Davis had selected several of the actions she wanted to use and had begun to organize them in fixed sequences. She wanted to resolve "traffic problems" and to make sure that actions would occur through the whole space. More importantly, the piece had a clear structure: The first part, "warm," would

feature a projected image of a camel and would be relatively more active; the second, "cool." with a projected image of a stag in a snowbank, would have a more dispersed energy, suggesting decay or entropy, the aging of a system.

It was only after we arrived in the gallery that we were able to see the real shape of Vanishing Acts. Davis had filled the large windows with a fiber optic cable system that represented the constellations of October's north sky. On the opposite wall, the elevator doors were covered with green astro-turf. Sky and earth were thus presented as vertical planes bracketing performers and audience, our usual sense of ground and circumstance turned on a 90-degree angle.

Photo: Martha Davis

Lights not available in the rehearsal space became important. The gallery's 38-lamp ceiling grid was used for area lighting and special effects, hanging

"trouble" lights provided local lighting for certain areas, performers worked with flashlights in several actions, and a follow-spot served to focus attention on other actions. A miniature city, which appeared to float in the air above the pool (it was actually set atop a blackened platform in the water), was lit up some minutes into the first part; in the second part, I used wooden matches to make a miniature campfire.

Finally, there was water! At the beginning of the piece, a sprinkler attached to a hose moved back and forth over the pool and bridge. Later, the sprinkler head was replaced by a nozzle and I was able to develop an action with another performer by spraying an arch over the bridge while he walked across it. It was only during the fourth of the five consecutive performances that we fully resolved this action. At the other mover's suggestion, I lowered the arch so that the water struck his face as he walked through it. The surprise and the effect of the sound gave the incident a density we liked.

I describe our work on this action to indicate that the piece was always "in process." Although the various actions were set, one could continue to explore ways of completing them. Another example: At the beginning of the piece I rose vertically, very slowly. from behind the slope, moved down it and across the platforms in the pool, and arrived at the floor in front of the audience in a horizontal position. The action became slower each night we did the piece. In the last performances I couldn't make it to the floor in the allotted time; instead I lay prone across the platforms.

Sometime early in the improvisation sessions, Davis had asked each of us to do something with the blackboard for five minutes. One mover drew a grid and made handprints with water; the other two treated it as an object and moved around, through, and over it. Near the blackboard I saw a pail of water with a sponge. I simply placed the pail on the chalk ledge and spent five minutes experimenting with ways to squeeze water out of the sponge. Although I found my action rather boring. Davis decided to use it. She coupled it with one mover doing a dance improvisation to Telemann's Water Music, another mover leaping on the slope, and the fourth mover working with a map and a flashlight on the ladder's platform.

Robert McKaskell in Vanishing Acts. Photo: Martha Davis

While I understood her reasons for wanting simultaneity, I didn't understand why she chose my squeezing water from a sponge as an action. As I did it more often, though, I found the action more and more interesting and variable, and I became involved with providing a foil to the music. In the gallery, I thought of the water dripping from the sponge as a momentary vertical flow to balance the obdurate horizon of the pool. Then it came together for me. At the end of the piece there was a film of Niagara Falls. My small drips were the human complement to nature's huge gush.

But no. This is only interpretation, and I mistrust the simplicity of the parallels.

"Actuality," George Kubler wrote, "is when the lighthouse is dark between flashes; it is the instant between the ticks of the watch: it is a void interval slipping forever through time: the rupture between past and future: the gap at the poles of the revolving magnetic field, infinitesimally small but ultimately real. It is the interchronic pause when nothing is happening. It is the void between events. Yet the instant of actuality is all we ever can know directly." (3)

It was the experience of squeezing the sponge that mattered, and the thoughts of those who witnessed it.

For thirteen minutes between the first and second parts of Vanishing Acts the gallery was dark. Four letters that Davis had written to someone important who figured at one time in her life were transmitted across an LED message board. The letters were very different from one another, each emerging from a specific kind of memory or projection. All were equally "real." As she wrote in her notes, "Autobiography - your inner self - is what you've got." Everyone's autobiography is different, of course, but like the instant of actuality, one's own autobiography is constantly changing, constantly occurring in a rupture between past and future.

HOW THEY LOOKED FOR YOU ON THEIR WAY BACK, DOWN ALONG THE PALISADES TO THE CITY, BUT YOU NEVER APPEARED

HOW YOU NEVER OFFERED AN EXPLANATION OR AN APOLOGY. THAT DAY WAS ALIVE AND VIVID IN THEIR MEMORIES.

HOW LIKE YOU, THEY SAID, SHAKING THEIR HEADS._ _ _ _ YOU REMEMBER ALL THAT?_ _ _ _ PROBABLY NOT.

It seems to me that the moment of doing or watching performance art provides a heightened, more memorable, fixed rupture, and that this notion probably motivated performance art twenty-five years ago.

NOTES

1. Some implications are obvious: Is this a representation of an audition? If so, is the performer who is named the chosen one? Or are the performers passing time, dropping off to sleep while waiting to be called? I was once a violinist. Before beginning a recital I would sit off-stage, drawing my bow across one string so slowly that no sound would vibrate. When I completed the movement, I knew my bow arm was "in shape", and that my adrenal flow was in control. Are the performers doing a warm-up exercise?

2. The Drama Review, Vol. 29, no. 2. Cambridge, MIT Press, quoted as DR followed by page number.

Physics and the Ultimate Significance of Time, "Bohm, Priogine, and Process Philosophy," ed. David R.Griffin Albany, N.Y., State University of New York Press, 1986, quoted as PST followed by page number.

3. Kubler, George: The Shape of Time, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1962, p. 17.