It is fairly well known that for the last 30 years, my main work as an artist has been located in activities and contexts which don't suggest art in any way.

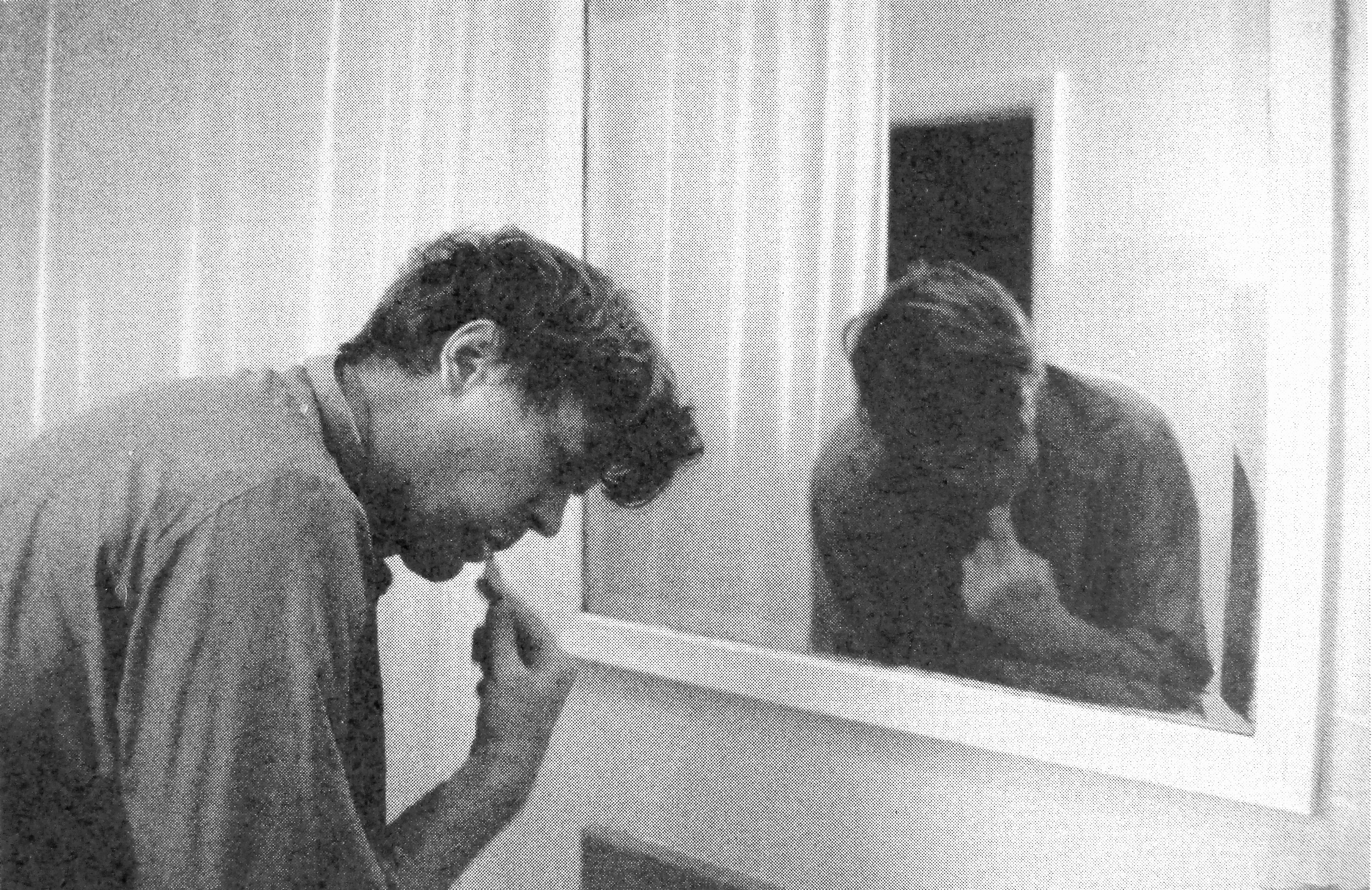

Brushing my teeth, for example, in the morning when I'm barely awake: watching in the mirror the rhythm of my elbow moving up and down...

The practice of such an art which isn't perceived as art is not so much a contradiction as it is a paradox. Why this is so requires some background.

Photo: Jeffrey Greenberg

When I speak of activities and contexts which don't suggest art, I don't mean that an event like brushing my teeth each morning is chosen and then set into a conventional art context, as Duchamp and many others since him have done. That strategy, by which an art-identifying frame (such as a gallery or theater) confers "art value" or "art discourse" upon some non-art object, idea, or event was, in Duchamp's initial move, sharply ironic. It forced into confrontation a whole bundle of sacred assumptions about creativity, professional skill, individuality, spirituality, modernism, and the presumed value and function of high art itself. But later it became trivialized, as more non-art was put on exhibit by other artists. Regardless of the merits of each case, the same truism was headlined every time we saw a stack of industrial products in a gallery, every time daily life was enacted on a stage: namely, that anything can be estheticized, given the right art packages to put it into. But why should we want to estheticize "anything"? All the irony was lost in those presentations, the provocative questions forgotten. To go on making this kind of move in art seemed to me quite unproductive.

Instead, I decided to pay attention to brushing my teeth, to watch carefully my elbow moving. I would be quite alone in my bathroom, without art spectators. There would be no gallery, no critic to judge, no publicity. This was the crucial shift which removed the performance of everyday life from all but the memory of art. I could, of course, have said to myself "Now I'm making art!" But in actual practice, I didn't think much about it.

My awareness and thoughts were of another kind. I began to pay attention to how much this act of brushing my teeth had become routinized, non-conscious behavior, compared to the time I was first taught to do it as a child. I began to suspect that 99% of my daily life was just as routinized and unnoticed; that my mind was always somewhere else; and that the thousand signals my body was sending me each minute were ignored. I guessed also that most people were like me in this respect.

Brushing my teeth attentively for two weeks, I gradually became aware of the tension in my elbow and fingers (was it there before?); the pressure of the brush on my gums, their slight bleeding (should I visit the dentist?). I looked up once and saw, really saw, my face in the mirror. I rarely looked at myself when I got up, perhaps because I wanted to avoid the puffy face I'd see, at least until it could be washed and smoothed to match the public image I prefer. (And how many times had I seen others do the same and believed I was different!)

This was an eye-opener to my privacy and to my humanity. It was an unremarkable picture of myself that was beginning to surface, an image I'd created but never examined. It colored the images I made of the world, and influenced how I dealt with my images of others. I saw this little by little.

But if this wider domain of resonances, spreading from the mere process of brushing my teeth, seems too far from its starting point, I should say immediately that I never left the bathroom. The physicality of brushing, the aromatic taste of the toothpaste, rinsing my mouth and the brush, the many small nuances such as my right-handedness causing me to enter my mouth with the loaded brush from that side and then move to the left side - these particularities always stayed in the present. The larger implications popped up from time to time during the subsequent years. All this from toothbrushing.

How is this relevant to art? Why is this not just sociology? It is relevant because developments within modernism itself led to art's dissolution into its life sources. Art in the West has a long history of secularizing tendencies, going back at least as far as the Hellenistic period. By the late 1950's and 1960's this lifelike impulse dominated the vanguard. Art shifted away from the specialized object in a gallery, to the real urban environment; to the real body and mind; to communications technology and to remote natural regions of the ocean, sky and desert. Thus, the relationship of the act of toothbrushing to recent art is clear and cannot be bypassed. This is where the paradox lies; an artist concerned with lifelike art is an artist who doesn't make art.

Anything less than paradox would be simplistic. Unless the identity (and thus the meaning) of what the artist does oscillates between ordinary, recognizable activity and its other role as "resonator" of the human context beyond that activity, it reduces to only conventional behavior. Or if it is framed as art by a gallery, it reduces to only conventional art. Thus, toothbrushing, as we normally do it, offers no roads back to the real world either. But ordinary life performed as art/not art can charge the everyday with metaphoric power.