Excerpts from final address to QOSCO 87, 7th Group Theater Meeting, Urubamba, Peru, October, 1987. Translated by Richard Fowler

History is often compared to a river, to an impetuous current which sweeps everything along with it. There are those who believe it is possible to escape this current and they build houses on the two banks of the river. They believe that they will not be bothered by the current. But the river overflows and carries away animals, children, strong people, houses of cement.

An old man was living with his family near a river. One day he took his boat, went out on the water, rowed out to the middle where the current was strongest and stayed there. He did not return to land. Every day, his son brought him food and asked him to return to the house on the bank. The father stubbornly continued his rowing against the current. And in this way he continued day after day, year after year, until the night he died. At dawn the next morning, his son climbed into a boat and went out to the middle of the river to row against the current.

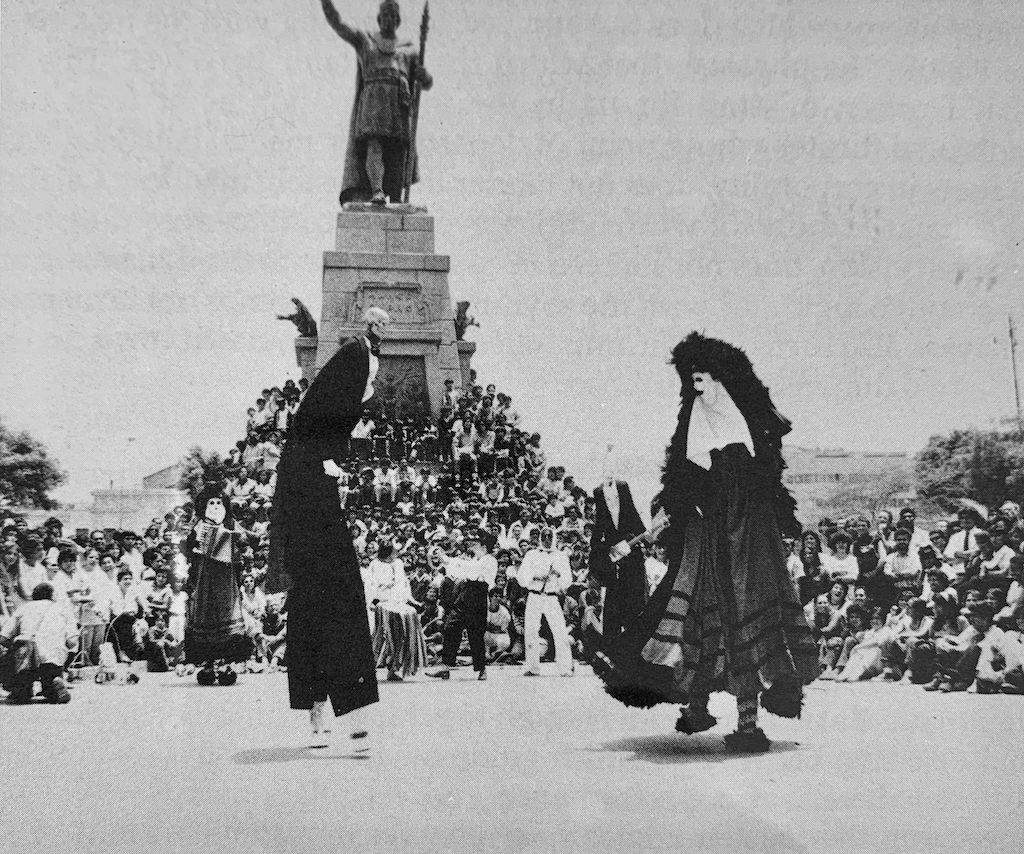

Group theater was created at the beginning of this century, in England, by women who were fighting for the right to vote, by the suffragettes. These women, in order to give more impact to their meetings, to condense the evidence of an unjust situation, turned to those who, because of their profession, had valuable public experience: actresses. In this way, theater groups composed of women were created. Their purpose was neither artistic nor aesthetic but rather was to give another meaning to this relationship we call theater.

The How: Technique

The word re-presentation, which is used to define performance, contains the idea of double presentation, of a doubling of the actor's presence as an historical being and as a professional. This presence is transformed by the spectator into sensorial experience and mental vision, into subjective sensation and articulated reflection. This "double presentation" always occurs in an historical context which determines its social effect and artistic value. This context is unique and at the same time relative. It cannot be transferred to other places without the representation changing its meaning, the most intimate nucleus of relationship with its spectators.

In order to be more effective in this context, in order to make his historical-biographical identity emerge, the actor uses forms, manners, behavior, procedures, guile, distortions, appearances...what we call technique. This is characteristic of every "performer" and exists in all theatrical traditions. Making an analysis which goes beyond cultures (west, east, north, south), beyond genre (classical ballet, modern dance, opera, operetta, musical, text theater, body theater, classical theater, contemporary theater, commercial theater, traditional theater, experimental theater, etc.), crossing through all this, we arrive at the first day, at the origins, when presence begins to crystallize into technique, into how to become effective with respect to the spectator.

We find two points of departure, two paths.

On the first path, the actor uses his spontaneity, the behavior which comes naturally to him, which he has absorbed since his birth in the culture and the social milieu in which he has grown up. Anthropologists define as inculturation his process of passive sensory-motor absorption of the daily behavior of a given culture. The organic adaptation of a child the conduct and life norms of this culture, the conditioning to "naturalness", permits a gradual and organic transformation which is also growth.

Stanislavsky made the most important methodological contribution to this path of spontaneity, or "inculturation technique." It consists of a mental process which "enlivens" the actor's incultured naturalness. By means of the "magic if", of a mental codification, the actor alters his daily behavior, changes his habitual way of being and materializes the character he is to portray. This is also the objective of Brecht's alienation technique or social gesture. It always refers to an actor who, during the work process, models his natural and daily behavior into extra-daily scenic behavior with built-in social evidence or subtexts.

Acting technique which uses variations of inculturation is transcultural. The "peasant" theater of Oxolotlan, made by isolated indigenous people on a mountain in Mexico, uses a technique which is based on inculturation. It is the same technique found in the Living Theater of Khardaha on the outskirts of Calcutta, where the actors are farmers, workers or students. There are ways of being an actor in Europe and America, in Asia and in Australia, which are manifest through inculturation technique.

At the same time, it is possible to observe in all cultures another path for the "performer": the utilization of specific body techniques which are different from those used in daily life. Modern and classical ballet dancers, mimes, and actors from traditional Oriental theaters have denied their "naturalness": and imposed upon themselves another means of scenic behavior. They have undergone a process of enforced "acculturation", imposed from the outside, with ways of standing, walking, stopping, looking, sitting, which are different from the daily ones.

The technique of "acculturation" artificializes (or "stylizes," as is often said) the actor's behavior. But, at the same time, it creates another quality of energy. We have all experienced seeing a classical Hindu or Japanese actor, a modern dancer or a mime. Such a performer is fascinating to the degree that s/ he has been successful in modifying his of her "naturalness", transforming it into lightness, as in classical ballet, or into the vigor of a tree, as in modern dance. The acculturation technique is the distortion of appearance in order to re-create it sensorially in a fresher, more real and more surprising way.

I use the term "performer" and not actor because on the path of acculturation it is impossible to distinguish the actor from the dancer. This is why, in the Orient, a dancer is also a singer and actor. The "accultured" performer manifests a quality and an energetic radiation which is presence ready to transform itself into dance or theater according to intention or tradition.

The path of inculturation does not lead to dance but rather to a richness of variations and shades of daily behavior and to an essential quality of vocal action, of the spoken. The path of acculturation makes it possible to arrive at the pre-expressive level: presence ready to re-present.

But we must not forget that acculturation is a colonization, the imposition, even if voluntary, of another kind of presence. Once it has been absorbed, it becomes a "second naturalness." We cannot free ourselves of it. Anyone who has worked as a mime or as a classical dancer moves and stops by means of determined dynamic discharges which condition the posture, the use and position of the spinal column, balance. Each detail is codified. Codification means formalization, precise form which must be respected. A pre-established pattern must be repeated. The dancer or the mime remains captive of these patterns.

It is interesting to see them struggle to free themselves from a learned technique and attempt to unlearn what took so many years to master.

The path of acculturation leads to codification, a formalized presence recognizable in a genre: ballet, mime, Kathakali, Noh. This formalized presence is necessary for anyone who wishes to express himself artistically through traditional genres. But for a performer in a contemporary performance who wishes to eliminate the boundaries between dance, theater, song, opera, circus...the most dangerous trap is to develop a formalized presence in a genre. It is essential to arrive at a presence which, respecting the transcultural principles which are found in all acculturation techniques, permits the construction of a personal technique, of a presence with personal codification.

This is the task of training: to leave psychology and the preoccupation with giving life to a character to one side, in order to concentrate on the construction of a presence with personal codification, an acculturation towards pre-expressive behavior.

The apprentice can follow the path of inculturation or the path of acculturation. The objective of both paths is totality, the meeting and integration of the complementary pole which at the beginning was not included: anyone who starts with a "magic if" or with whatever other mental process must materialize this process into presence which is sensorially perceptible to the spectator. And anyone who has acquired an accultured behavior must integrate his mental-emotional universe. One path is not better than the other. It would be myopic to think that theater of accultured technique is superior. No. The two paths have the same ravines into which the performer can fall: the ravines of empty forms, of technical stereotypes, of dynamic mannerisms. And the ravine of anemic forms on the corporal, sensorial, visible level in spite of social, poetic, psychological intentions.

The process becomes mutilated if it mobilizes only internal, invisible, mental energy which does not succeed in merging with the material, the visible, the physical, that which the spectator perceives. This is what is often missing for us in the inculturation actor form the traditional theater whose point of departure, or mental behavior, has no roots in corporality, does not render the invisible manifest. On the other hand, if the actor who codifies, even if he codifies according to a personal vision, does not succeed in connecting with the dynamism of his emotive logic and with the asymmetrical coherence of his mental behavior, also turns into an amputated being, a gymnastic toy, a circus act, a two dimensional virtuoso.

The Why: The Meaning

Looking back in time, I face the paths which I have travelled on, the condensed nuclei of events, books, meetings, voices, accidental sentences, incidents. By means of these I try to explain to myself why I do theater, why I continue to do it. The how of doing theater is important. But if I am lucky enough to achieve technical competence, and objective knowledge which guide me in the construction of the different levels of a performance and its relationships with the spectators, the question comes up again, even more imperatively: why do I do it? Because of exhibitionism? For money? In order to gain social prestige? In order to be someone whom men and women can admire, desire? In order to escape my condition, my skin, my thoughts? In order to help those who never asked to be helped? To change society?

I know that the theater can radically change something in society: itself, its way of behaving, of presenting itself, or re-presenting itself. I know this because the many paths back to my origins demonstrate it. Looking back, towards the first day, I meet Grotowski, my elder brother. I could also call him my father, my grandfather, my totem. It doesn't matter. The essential thing is to recognize the filial connection and be proud of it. At his side, I learned certain fundamental principles about how to make theater. More exactly: at his side, I intuited the personal meaning of the profession, why one makes theater.

In the early Sixties in Poland, the authorities imposed production norms, a pre-established number of performances and openings for each season. It was the quantity which was important, how many spectators, how many performances. Human beings, particular and unique, did not exist. They were cattle, sheep. This frenzy of production and quantity, this illusion of numbers and statistics was called cultural politics, democratic culture, popular theater. Grotowski did not want to make eight, six, three, new productions a year. He wanted to prepare just one, but well. To give the maximum. To present it to a limited number of spectators in order to maximize the communication. To establish with these few spectators spatial and emotional relationships which constituted an encounter, a dialogue with themselves, a meditation on the times. In order to fulfil his personal necessity, he had to fight against the times, he had to travel back down the paths towards the origins and re-discover, in his ancestor Stanislavski, the theater as a laboratory, as a privileged place for the creation of new relationships. Grotowski's "poor theater" was not a technique, a "how" to make theater. It was why he was doing it.

In this period, in 1961, 1962, 1963, sometimes only three or four people came to his performances. During the three years that I stayed with him, I witnessed that his resistance was only for a handful of spectators. It was this stubbornness of Grotowski's, his rowing against the current, which revealed to the theater of our age anther way of being social, or taking a stand, of being loyal to the values of one's own identity.

One of the most moving and ambiguous myths in Western civilization tells the story of a man who is searching for his origins. On the path towards his identity he kills his father, sires sons/brothers on his mother, brings the plague down upon an entire population. He goes into exile. But someone follows him, an adolescent: Antigone. Years later, when she goes back to her city, Thebans confront Thebans, brothers enjoy torturing bothers, children carry arms, have learned to slaughter. Violence and horror: Thebes is the heart of darkness.

Confronted with the civil war in which her brothers have killed each other, Antigone takes a stand. She does not defend her uncle Creon and the law of the state which he represents. Neither does she take to the hills to join her brother's army in the war against the state. She knows the role she has chosen. And she acts in a way that allows her to be loyal to her role. She leaves the city by night and goes to the countryside, takes a handful of dust and scatters it over her brother's corpse, to which Creon has refused burial. A symbolic ritual, empty and ineffective against horror. Which she nevertheless does because of personal necessity, and pays with her own life.

Antigone's handful of dust, Grotowski's handful of spectators. What ridiculous actions with which to resist the times and row against the currents. But we cannot erase these actions from our memory. They are in the origins, and impel us to continue day after day in spite of isolation, lack of consideration, modest results, danger. This is the theater: an empty and ineffective ritual which we fill with our "why," our personal necessity. Which in some countries on our planet is celebrated with general indifference. And in others can cost the lives of those who do it.

I think that the actors of Odin Teatret and I belong to the same species as the old man who left his family, set off from the bank, and out in the middle of the river, rowed against the current. It would appear that the inhabitants of the banks who laughed at us were right. Twenty-three years have gone by, there are many wrinkles on our faces, we are turning grey, we feel the exhaustion of the years and of the profession. But now we are no longer alone. Behind our boat, there are others. There are others beside us, faces, we are turning grey, we feel the exhaustion of the years and of the profession. But now we are no longer alone. Behind our boat, there are others. There are others beside us, others in front of us. We are a little flotilla in the center of the river. We are the third bank. The day when the river gets rough, it's going to sweep us away. But also, along with us, the big buildings with their plush seats and bright lights which are there, on the two banks.

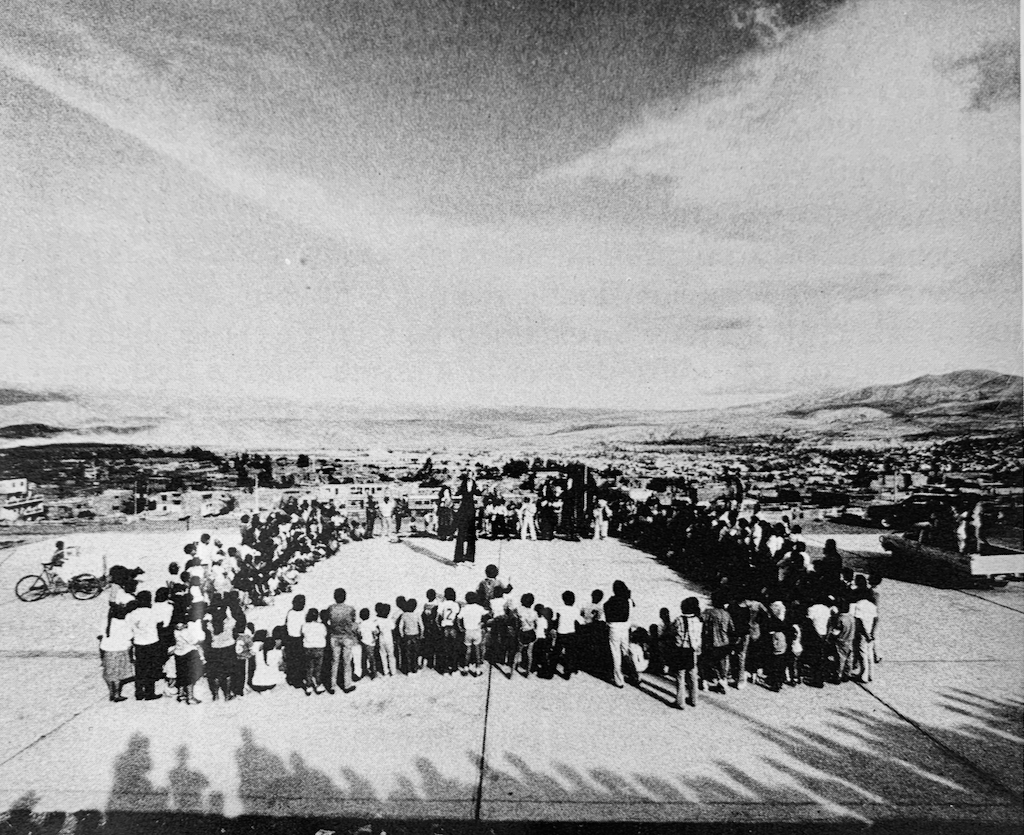

To learn to resist, this is what I have seen here at QOSCO 87, nine years after Ayacucho. I look at you and I feel a deep pride: you have known how to make yourselves individuals who know how to be performers and why.

I belong to a theatrical family whose grandmothers are Antigone a Edy Craig. This same family has other members... adolescents w speak different languages, who act in different ways, who go opposite directions, who have never met me, who barely catch glimpse of me through the stories or the examples of other theat groups. it is a family which knows its origins, which knows how recognize its ancestors, its elder brothers, which does not forget origins. Which refuses to collaborate with the society of amnesi Which wants to represent the memory of the times, aware that th memory which can be shown is a symbolic action for a handful spectators.

This is why, when in Brazil listening to a version of Guimaraes Roas story, The Third Bank of the River, I intuited the why of so many year of work. And why, in Belgrade, in 1976, I called Odin Teatret and th other groups by another name, the kind of name we give to a perso dear to us: Third Theater.